As I've woken up a bit recently to get back to what I truly love, poetry, editing the genre for The Nervous Breakdown (TNB), and writing with a consistency I last remember from years ago, I've had some very kind requests for me to share some of my poetry. I've decided to start with a small collection of poems that already appear on the 'net in one form or another, some of which were published in journals, and some of which I just put up myself.

"Growing up Misfit" (2010, published in TNB) I captioned this: "Uche writes a poem about his adventures constantly moving, and never fitting in." It was my debut poem on TNB, having done a lot of talking about poetry prior to publishing that. I wrote it specially for a reading at the TNB New York live event to which Kimberley kindly invited me. Look on the upper right hand of the page for an audio of my reading a somewhat older version of the poem. "Mountain Summer" and "Fever Pitch Tent" (1995, published in ELF: Eclectic Literary Forum) Soon after I graduated I took a road trip with friends, flying into Ft. Collins, Colorado, and driving to San Francisco. It is on that trip that I fell in love with Colorado and resolved to move here as soon as I could. It was a trip full of marvelous memories of friendship and adventure, which I captured in a few poems, three of which were published in ELF: Eclectic Literary Forum, my favorite poetic journal, and sadly long defunct. (BTW if anyone knows of an current journal with similar aesthetics to those established by ELF's Cynthia Erbes, please let me know). "Supermarket Perimeter" (2007, published in Fiera Lingue) As I recall I happened to be flipping channels one day and caught a bit of a reality TV show where a fitness guru was teaching a slovenly youth about eating well. She told him "the trick to supermarkets is that all the healthy food is on the outside..." That's probably a commonplace, but nothing I'd really thought of before. I was immediately struck by the idea that a modern lesson about healthy eating might be packaged so completely into the boundary of a supermarket. I was inspired to have a little fun with the phenomenon. "Carotid" (2005, unpublished) Not much really to say about this one. It just sprang from one of those magical moments."Eliot" (2005, published in Fiera Lingue) I've written several poems about major influences in my poetical career, and one of these concerns T.S. Eliot, who is a most ambiguous figure for me, as reflected in this poem, and as I've often mentioned here on Copia. I've put a lot into study of his impeccable craft, but as a Humanist I find myself appalled by his misanthropy (and its apparent wellspring in misogyny and other bigotries). "Sappho and Old Age" (2010, published in TNB) We have weekly features in the TNB poetry section. One week we learned that our scheduled feature had fallen through. I'm not sure what possessed me (rimshot) but I decided to build a feature around my translation of Sappho's Tithonus poem, which I squeezed into the two days prior to deadline. Here are some more notes on the effort. I have a few more poems coming out here and there in a month or two, and I'll post links in comments as they emerge. I really haven't been submitting my poems about (it's just so much work to pile upon everything else I juggle), and this year's opportunities have pretty much fallen in my lap. I guess I should get around to finding at least a little time for the submissions grind.One of my favorite quotes is from one of my greatest idols, Nigeria's great writer and Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka: "A tiger does not proclaim its tigritude. It pounces." This tiger of a story [Who Fears Death] definitely pounced on me without proclamation or warning. I'm glad I was ready for it.

—Nnedi Okorafor—"The Tigritude of a Story"

Soyinka's famous quote, made in response to the Négritude movement of Senghor, Césaire, and other Francophone African writers has always resonated with me as well. Afrocentrism that spends most of its time contemplating its own plumage was perhaps inevitable in those early days, so soon after the colonial yokes had been thrown off. But having been immersed in our own reality, having, as Nnedi also mentions, endured wars of desperation such as the Biafran, having lived to see our resources squandered and the legacy of revolutionary leaders turned despots, we're past time for preening. If we plan to survive, it's well past mealtime. We'd better pounce. To be fair, Négritude never really took off in Anglophone Africa. In "Christopher Okigbo," Sunday Anozie quotes a letter sent to him by the great Nigerian poet. In 1966 Okigbo had been invited to the Negro Festival of Arts in Dakar, where his poem Limits was awarded first prize. Okigbo wrote:About Dakar. I did not go... I found the whole idea of a negro arts festival based on colour quite absurd. I did not enter any work either for the competition, and was most surprised when I heard a prize had been awarded to Limits. I have written to reject it.

As Anozie says, "This sums up Okigbo's whole attitude to the color stress in Négritude." Soyinka's reaction was of the same kind. Anozie does actually surprise me by going on to claim that Okigbo's objections are ultimately shallow, and Soyinka's "cynical." To be honest, I find a lot that annoys me in Anozie's book, overall, but he also does more to plumb Okigbo's depths than anyone else I've seen, so it's still well worth a read.

By the way, Nnedi says:

Amongst the Igbos, back in the day, girls who were believed to be ogbanjes were often circumcised (a.k.a. genital mutilated) as a way to cure their evil ogbanje tendencies.

I had heard of female circumstances in parts of Igbo land, but I hadn't heard of its use as a counter to Ogbanje. I wonder whether that custom was widespread in Igbo land (as for example destruction of twins was a custom more in the far south than elsewhere). Time to ask our elders some straight questions.

Her face Her tongue Her wytt

So faier So sweete So sharpe

first bent then drewe then hitt

myne eye myne eare my harteMyn eye Myne eare My harte

to lyke to learne to love

her face her tongue her wytt

doth leade doth teache doth move Her face Her tongue Her wytt

with beames with sounde with arte

doth blynd doth charm doth knitt

myne eye myne eare my harteMyne eye Myne eare My harte

with lyfe with hope with skill

her face her tongue her witt

doth feede doth feaste doth fyllO face O tongue O wytt

with frownes with checks with smarte

wronge not vex nott wounde not

myne eye myne eare my harteThis eye This eare This harte

shall Joye shall yeald shall swear

her face her tongue her witt

to serve to truste to feare.

—Sir Arthur Gorges—"Her Face"

Ring out your belles, let mourning shewes be spread,

For love is dead:

All Love is dead, infected

With plague of deepe disdaine:

Worth as naught worth rejected,

And Faith faire scorne doth gaine.

From so ungratefull fancie,

From such a femall franzie,

From them that use men thus

Good Lord deliver us.

And thus in the remaining stanzas.

He scarce had ceas't when the superior Fiend

Was moving toward the shoar; his ponderous shield

Ethereal temper, massy, large, and round

Behind him cast; the broad circumferance

Hung on his shoulders like the Moon, whose Orb

Through Optic Glass the Tuscan Artist views

At Ev'ning from the top of Fesole,

Or in Valdarno, to descry new Lands,

Rivers or Mountains in her spotty Globe.

His Spear, to equal which the tallest Pine

Hewn on Norwegian hills, to be the

Mast Of some great Ammiral, were but a wand,

He walkd with to support uneasie steps,

Over the burning Marle, not like those steps

On Heavns Azure, and the torrid Clime

Smote on him sore besides, vaulted with Fire;

Nathless he so endur'd, till on the Beach

Of that inflamed Sea, he stood and call'd

His Legions, angel Forms, who lay intrans't

Thick as Autumnal Leaves that strow the Brooks

In Vallombrosa, where th'Etrurian shades

High overarcht imbowr;…

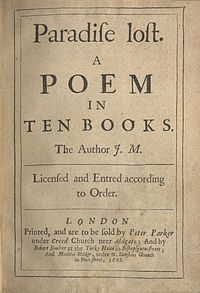

—John Milton—from Book 1, Paradise Lost, quoted in "Eliot & Milton Studies", Sherry, Beverley, Versification 5 (2010)

I finally caught up with the new edition of Versification, (presently the front page of the site) a bit of Sunday morning therapy through prosody. The first article, on the possibly exaggerated modernist credentials of Emily Dickinson, is a bizarre thing that seems to want to be edgy and cool, spending time comparing Dickinson to a visual poet who played at Möbius strip-mining with Eikon Basilike (a bit of a look-forward to the later Milton piece), and with whom there is no conceivable connection. It also does go on about an apparent saw that you can sing all Dickinson's poems to the theme of Gilligan's Island, an rather sophomoric bit of pablum. The second article is a punctilious, frequently baffling, over-argued, and generally dreary exposition of pervasive syllabic verse in W.H. Auden.

Luckily I persevered because the last two pieces were true delights. The last article is a review of Latin Word Order: Structured Meaning and Information, by Devine and Stephens (Oxford University Press, 2006). It sounds like a wonderful volume, and I've added it to my Amazon wish list for whenever I can afford the $85. Any book that dwells with insight over the contrasting word order of socerum tuae filiae versus filiae tuae socerum is irresistible to a language geek. The third article, "The Legacy of T.S. Eliot to Milton Studies" discusses "the Milton controversy" of the twentieth century, triggered by Eliot's early attacks on Milton. I've never seen the controversy as a big deal. In my own taste I go from enjoying Milton's earlier "L'Allegro" and "Il Penseroso" to admiring but not at all enjoying his magnum opus "Paradise Lost." I certainly understand the urge by Eliot and cohort to elevate Donne and the Metaphysics, cavalier spirits of rotund urbanity, compared to the dour asceticism of old Roundhead Milton (and yes, I know The New Critics would have shied away from such biographical tinting, but I'm not really one of them), but many of their specific criticisms have never really been credible, and this article presents a useful survey of the vigorous response to the anti-Milton camp. One flaw I found is in Sherry's lumping in with the New Critics Robert Graves's own anti-Miltonism, best known from his novel Wife to Mr Milton. It's important to separate Grave's objections, which were more on moral grounds tha n on prosodic, from Eliot, whose objections focused on his poetics. The Graves who wrote the "These be thy Gods, O Israel!" lecture would be furious to find himself lumped in with the agenda of "the 'most 'significant' modern writers." Mr. Triple Goddess Graves could never tolerate any betrayal of the women in a poet's life, despite the fact that his own relationship with Laura Riding included every usual human frailty. As far as he was concerned, Eliot's sins were even more foetid than Milton's. Graves's own words, in "The Ghost of Milton," which he wrote in response to criticism of his treatment of Milton in Wife to Mr Milton:My attitude to Milton must not be misunderstood. A man may rebel against the current morality of his age and still be a true poet, because a higher morality than the current is entailed upon all poets whenever and wherever they live: the morality of love. Though the quality of love in a painter's work, o a musician's, will endear him to his public, he can be a true painter or musician even if his incapacity for love has turned him into a devil. But without love he cannot be a poet in the final sense. Shakespeare sinned greatly against current morality, but he loved greatly. Milton's sins were petty by comparison, but his lack of love, for all his rhetorical championship of love against lust, makes him detestable.

With all possible deference to his admirers, Milton was not a great poet, in the sense in which Shakespeare was great. He was a minor poet with a remarkable ear for music, before diabolic ambition impelled him to renounce the true Muse and bloat himself up, like Virgil (another minor poet with the same musical gift) into a towering, rugged major poet. There is strong evidence that he consciously composed only a part of Paradise Lost; the rest was communicated to him by what he regarded a supernatural agency.

The effect of Paradise Lost on sensitive readers is, of course, overpowering. But is the function of poetry to overpower? To be overpowered is to accept spiritual defeat. Shakespeare never overpowers: he raises up. To put the matter in simple terms, so as not to get involved in the language of the morbid psychologist: it was not the Holy Ghost that dictated Paradise Lost—the poem which has caused more unhappiness, to the young especially, than any other in the language—but Satan the protagonist, demon of pride. The majesty of certain passages is superhuman, but their effect is finally depressing and therefore evil Parts of the poem, as for example his accounts of the rebel angels' military tactics with concealed artillery, and of the architecture of Hell, are downright vulgar: vulgarity and classical vapidity are characteristic of the passages which intervene between the high flights, the communicated diabolisms.

the sound of the poem is magnificent; only the sense is deficient.

Which seems to echo Eliot's objections, but Graves goes on to clarify his quarrel with the sense, and it turns out to be a Pagan Celtic sanctimony every bit as fulsome as the Christian sanctimony of his quarrel with Paradise Lost. Again nothing to corroborate Eliot's points in substance.

I suppose the upshot of today's reading is that I'll be spending a bit more time revisiting Milton's actual text, but unless I suddenly find him much less soporific than I did when I made a serious attempt to appreciate him in the past, I'm not going to pretend I have the stamina for much of his work. The point of escaping into poetry is to enjoy the amenities of the alcove, a notion I would have thought was obvious, but which I've had to suggest to others several times, recently.

Thanks very much to those responsible for Versification for having giving me these hours of enjoyment and reflection. It must be a truly thankless task to produce a journal on Prosody these days.

✄ ✄ ✄

Editorial note: You might have noticed I expanded the title of this post beyond the customary "Quotīdiē." I plan to continue doing so.

So I never could tell where you

Put your foot, your root,

I never could talk to you.

The tongue stuck in my jaw.It stuck in a barb wire snare.

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

I could hardly speak.

Sylvia Plath — "Daddy"

An engine, an engine,

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

With my gypsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack

I may be a bit of a Jew.I have always been sacred of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo.

And your neat mustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue.

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You----Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you. ...And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf lookAnd a love of the rack and the screw.

In considering the charge against this device, I separate aesthetic grounds from moral grounds. Some people have a strong moral objection to making any comparison against the Holocaust. I reject that objection just as I reject all sacred oxen. Every experience, regardless of how horrible, is open to us as a device for self-expression. That is a fundamental basis for empathy. We can and should argue degrees in action and suffering, but we should never be forbidden to enter into such arguments in the first place. There is also my wariness of convention that confines the Holocaust to Jewish experience. Not for nothing does Plath mention her "gypsy ancestress", and I read the line "I may be a bit of a Jew" entirely as a metaphor.

That brings me to aesthetic grounds. I agree with the argument that Plath's comparisons tend towards the the grotesque, and it is only her immense expressive skill that rescues it. In general, Plath cannot escape the charge of egotism that goes hand in hand with the confessional movement. What redeems Plath is that her craft and command of words overwhelms and infact elevates her regular meanness to something that escapes escape the trivial quality of her peers. Her poetic faculties expand her work beyond the microscopically narrow paysage in which she threatens to trap the reader, who thus ends up with entire worlds of insight at his unexpected disposal. It's tempting to wonder what Plath might have accomplished had she not fallen so deeply into the school of confessional poets. If she had elevated her themes, as even her husband and tormentor generally attempted; could she have been as definitive in expressing her times as, say, Sappho? Then again that might be ridiculous speculation, because it's quite likely that her style suited the mean more than the large. "Daddy" is indeed over the top, but it is hard to imagine a better way to express the overwhelming extent to which marriage to Ted Hughes suffocated her in a coffin telescoping at its long polygon to her father, and at its short polygon to her suicide. In reading it even as an impressionable teen, I never thought for a moment that her personal tribulations came close to the sufferings of Hitler's genocide victims (Jews and otherwise). Yet the savage insistence of the metaphors did bring to a gut level her overwhelming despair with an intensity so extraordinarily difficult to accomplish through any other means. I think that is what poetry must deliver, even if it sometimes strains natural correspondences in the effort.I find it interesting to compare Plath to another poem about a broken marriage, one widely admired, and by no less than E.A. Robinson, "Eros Turannos."She fears him, and will always ask

What fated her to choose him;

She meets in his engaging mask

All reasons to refuse him;

But what she meets and what she fears

Are less than are the downward years,

Drawn slowly to the foamless weirs

Of age, were she to lose him.

...

The failing leaf inaugurates

The reign of her confusion:

The pounding wave reverberates

The dirge of her illusion;

And home, where passion lived and died,

Becomes a place where she can hide,

While all the town and harbour side

Vibrate with her seclusion.

I respect Robinson's effort, and the tidiness of his verse is almost heroic, with each line refusing enjambment and perpetuating a series of small finalities. I have a soft spot for such virtuosity, but I think that "Daddy" demonstrates by contrast the power of immediacy at all costs.

Plath's influence on me is very profound. It was really study of Plath that allowed me to grow into acceptance of free verse. So many of the other high priests of free verse, in English and French, including Whitman, Ginsberg and Kahn, left me utterly cold, though recently I've been able to appreciate these a little more. I never believed that LaForgue, Eliot and Pound took as much freedom many claim, and it was Plath, who really showed me that craft and free verse were not incompatible. She made it possible for me to listen properly to the great African poets such as Senghor, Césaire, Okigbo and Brutus for the first time. I wander through my own Journey in Plath (and Hughes), and how it relates to my family in "Slender Mitochondrial Strand". "Morning Song" for Udoka and "Metaphors" for his mother are my touchstones upon the birth of my third child.

Having said all that, I think it's perfectly fair for someone to find "Daddy" too grotesque for their taste, and in such cases, I tend to recommend "Mushrooms" instead.

Soft fists insist on

Heaving the needles,

The leafy bedding, Even the paving.

Our hammers, our rams,

Earless and eyeless, Perfectly voiceless,

Widen the crannies,

Shoulder through holes. We Diet on water,

On crumbs of shadow,

Bland-mannered, asking Little or nothing.

So many of us!

So many of us!

Our kind multiplies: We shall by morning

Inherit the earth.

Our foot's in the door.

I'm always tickled by the near-May-Day snows we get here in the Boulder area, and in 2005 I even wrote a poem (a bagatelle, really) "May Day Flakes" when we got a good 8 inches at the end of April. This morning we got a dusting, making it the latest in the year I've seen snow in the backyard. Early last week we got a few inches.

Our winters are generally so mild (though this past one was rougher than most) that my Nigerian blood doesn't curdle over at such oddities. In fact, we always get so much sun that all the snow is usually gone by afternoon of the day. Pico-season. Peek-a-boo season.

I'd meant to post this entry here on Copia.

To belong? What's it mean? Is it creature of tense? Is it active or passive?My recital of my poem, "Growing up Misfit", from the Spring, 2010 TNB Literary Experience in New York, is the lead piece in this week's TNB Podcast Feature on The Nervous breakdown. "TNBLE - Episode 7, Part I. The Nervous Breakdown's Literary Experience, recorded live in New York City at Happy Ending Lounge on 26 March 2010. Featuring Uche Ogbuji, Daniel Roberts, Tod Goldberg and Kristen Elde. Produced by Aaron M. Snyder and Megan DiLullo. Music by Goodbye Champion."

Is it cold set in bone, magma oozing to plate ocean floor, or explosive

Crackling reaction, plume clearing to flesh jacked into the massive?...Hussein's family had fled Iran in retreat from the Ayatollah muhajideen

But became the yard's only-good-one-is-a-dead-one once the hostage crisis went down.

Hussein had seen worse than punk clique kids. He was like: "Bring that shit on!"...When your eyes learn to look beyond state, to peers beyond infinity,

Okigbo, Villon, Pound, Plath, sometimes you forget that misfit can grow to vanity.

I've come to grow into readiness for company, the scent and crinkled space of shared humanity.

I've revised the poem a bit since that recording, but it's nice to hear the audio so crisp. Major props to Kimberly and her peeps at the event, and Megan and her peeps for the post-event production. I don't think I've ever heard myself so clearly.

Last week I suggested to my fellow TNB poetry editors a lark: I would post a Sappho poem for the week's feature, and a faux-self-interview as the poetess. April Fool's week might have been best for that, but I figured, what the heck, and my other editors liked the idea, so I set to work.

I had decided from the start that I would work on my own translation, and I thought it would be best to take on the Tithonus lyric, woefully incomplete until archaeologists found that famous strip from an Egyptian mummy wrapping in 2004. Based on the translations I'd seen so far, I thought it was perhaps worth it to go for a fresh take. I spent some time feverishly revising my Homeric Greek, knowing full well that even brushed-up Homeric or Attic comprehension would struggle with Sappho's Aeolic, but I had the Perseus on-line word study tool to get me further, and Google when I really needed a sniper shot. The result is "Sappho and Old Age".

On another, more well-known dispute, I claimed a bit more poetic authority. I went with the "ἰο κόλπον" of Prof. West's own reconstruction, rather than the "ἰο πλόκων" or "violet-wreathed" that West swapped in for his translation. The latter is a more conventional epithet, but as others have pointed out with the famous modulation of the Homeric "Ἠὼς ῥοδοδάκτυλος" ("rosy-fingered Eos/dawn") to the Sapphic "βροδοδάκτυλος σελάννα", ("rosy-fingered Selene/moon",) Sappho has always infused such allusions with her own originality. Like everyone, I've heard before that Plato lauded Sappho the tenth Muse, but I went looking for the citation, and all I could find was the mention I already knew, put by Plato into Socrates mouth in Phaedrus 235c.

νῦν μὲν οὕτως οὐκ ἔχω εἰπεῖν: δῆλον δὲ ὅτι τινῶν ἀκήκοα, ἤ που Σαπφοῦς τῆς καλῆς ἢ Ἀνακρέοντος τοῦ σοφοῦ...

I cannot say, just at this moment; but I certainly must have heard something, either from the lovely Sappho or the wise Anacreon... (Fowler translation)

It was fun revising that bit, though, as it led me to Prof. Pender's Sappho and Anacreon in Plato’s Phaedrus, but that can't be it. Can anyone shed better light on the "tenth Muse" laud?

To bring the dead to life

Is no great magic.

Few are wholly dead:

Blow on a dead man's embers

And a live flame will start.Let his forgotten griefs be now,

And now his withered hopes;

Subdue your pen to his handwriting

Until it prove as natural

To sign his name as yours.Limp as he limped,

Swear by the oaths he swore;

If he wore black, affect the same;

If he had gouty fingers,

Be yours gouty too.Assemble tokens intimate of him —

A seal, a cloak, a pen:

Around these elements then build

A home familiar to

The greedy revenant.So grant him life, but reckon

That the grave which housed him

May not be empty now:

You in his spotted garments

Shall yourself lie wrapped.

—Robert Graves—"To bring the dead to life"

It has been a sad long while since I've posted a Quotīdiē, and an even sadder long while since I've had time for contemplation of the choicest art, but few spirits raise raise me from a poetic torpor as well as Robert Graves, one of my favorite poets and critics.

Robin Hamilton used the first stanza of the above poem in a message on the New-Poetry mailing list. I couldn't place it, but when I asked Robin kindly provided the source.

I've invoked Graves myself on that mailing list. The man never seems far from modern meditation on the numinous qualities of poetry. He himself sometimes went overboard in his mysticism, and sometimes it even clogged up his verse (Robin put it very aptly: "God preserve us from Graves' Goddess Poems."), but overall, there are few writers that surpass Graves for impressing upon students the divine essence of poetry.

See for yourself. Visit the Robert Graves Archive. Some of the links therefrom are broken, but overall, it's a very useful compilation.

"Bullshit: invented by T.S. Eliot in 1910?"—Mark Liberman, Language Log

This entry discusses one of the conjectures for the origin of the word "bullshit", including discussion of a characteristically phlegmatic poem by T.S. Eliot. Eliot has always been a very nasty sort, and you can perceive that from far less than a reading of "Burbank with a Baedeker: Bleistein with a Cigar" or accounts of his treatment of his first wife, Vivienne. As with most student poets, I'm in awe of his genius, and intend to learn as much from him as possible in a literary sense, but I find him in many ways a personally despicable figure. Even Ezra Pound, who paid dearly for his own egotistic sense of mores, is a far more sympathetic figure. His punishment was excessive (especially considering the general hypocrisy of his prosecution), and he did repent much of his petty bigotry late in life.

I don't remember having ever seen the Eliot poem quoted in the above article, though I've found a lot of Eliot rarities. It's likely that if I did, I shrugged it out of my memory. It uses classic Ballade structure, three stanzas and an envoi, with an unconventional rhyme scheme (for the classic overall effect, see, for example, Villon's "L'Épitaph (Ballade des pendus)". Eliot translates the passion of Ballade into plain spite.

Ladies, who find my intentions ridiculous

Awkward insipid and horribly gauche

Pompous, pretentious, ineptly meticulous

Dull as the heart of an unbaked brioche

Floundering versicles feebly versiculous

Often attenuate, frequently crass

Attempts at emotions that turn isiculous,

For Christ's sake stick it up your ass.

Eliot—second stanza of "The Triumph of Bullshit"

Horrid genius. Eliot attaches several senses to "ladies", including (and this is the sense that does find best concord with the poem), the society matrons who influenced popular, and hence critical, taste. But Eliot is also a bit of a coward here. What is it that he did finally offer the "ladies", that made his fortune?

Time for you and time for me.

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.And indeed there will be time

To wonder, "Do I dare?" and, "Do I dare?"

Time to turn back and descend the stair,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair—

Sure he's still lampooning the Society of Taste, but he doesn't in public dare not to put himself under the glass as well, and seeks indulgence and sympathy as an object of ridicule.

There is also his extraction of Ophelia from Vivienne (or was that Viv doing herself?) from "A Game of Chess": Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night. Spoken with a knowing wink.

No, when it's time for brave, open sally, Eliot prefers weak targets. My thanks to Mark, though, for finding a poem that is as interesting as a badge of character and illustration of craft as it is an etymological marker.