The court awaited

As the foreman got the verdict from the bailiff,

Emotional outbursts, tears and smeared makeup.

They stated, he was guilty on all charges.

She's shaking like she took it the hardest—

A spin artist, she brought her face up laughing.

That's when the prosecutor realized what happened—

All that speaking her mind testifying and crying,

When this bitch did the crime—the queenpin...

—Common—from "Testify"— BE

Common is one of my favorite musicians, and so I'm really pleased to see his new baby, BE emerge to commercial success (#2 on the overall album charts in the week of release) as well as critical praise. I was in Amsterdam the week BE came out, and I was too busy to look for it there. I did see it at the Heathrow HMV on my way back home, but it was crazy-dear (excuse me? £13.00?). I bought Blak Twang's latest (The Rotton Club) at U.K. prices while there (can't get that ish in the US) but Common could wait 12 hours. I'm back and I've been listening to BE on heavy rotation for a week now.

Common is one of my favorite musicians, and so I'm really pleased to see his new baby, BE emerge to commercial success (#2 on the overall album charts in the week of release) as well as critical praise. I was in Amsterdam the week BE came out, and I was too busy to look for it there. I did see it at the Heathrow HMV on my way back home, but it was crazy-dear (excuse me? £13.00?). I bought Blak Twang's latest (The Rotton Club) at U.K. prices while there (can't get that ish in the US) but Common could wait 12 hours. I'm back and I've been listening to BE on heavy rotation for a week now.

A lot of fans have expressed relief that Common has retreated to home base. With Kanye West replacing former gurus No I.D. and Doug Infinite, BE feels like the extrapolation of the straight line from One Day It'll All Make Sense through Like Water for Chocolate, and Electric Circus ends up stranded as an outlier. Common has confirmed that he has turned his back on the crazy next ish of EC. From a recent AllHipHop.com interview:

AllHipHop.com: How would you rate your albums from least favorite to greatest?

Common: Well my favorite albums would have to be Like Water for Chocolate and BE, my second is Resurrection, and my third is One Day It Will All Make Sense and then, Can I Borrow a Dollar, and Electric Circus is my least.

This is very sad, and Common has taken a bad knock on the head when he rates EC lower than Can I Borrow a Dollar (the only Common album even I won't buy, not even used). I don't know whether to be happy that Common has released a tight album with BE or bitter that he has abandoned the risk that was so fertile in EC. I had intended this article to be a review of BE, but I couldn't help its turning into a sort of measuring of BE against EC. I've already rhapsodized about EC here so no doubt where I stand on that album. BE is a major swerve from EC.

Don't get me wrong. I love BE. It is a lot smoother than EC. It's much more focused. We've seen this pattern before. With Phrenology The Roots broke their bounds and put us on some next shit. After the same mixed critical and fan reaction (though much less bloodthirsty than the reaction to EC), the Roots backed off from the experimental and produced an extremely focused and cohesive The Tipping Point. BE is as tight, coherent and cohesive. The sonic texture is pure Chi-Town soul from track 1 through 11. Chi-Town soul is rich and diverse enough the this never leaves your ears tired, and each song has an ingenious little touch that sets it apart from the rest (an example apropos of the main quote is the plaintive battology of the sample in "Testify"). In contrast EC was all over the place sonically, and in one place, "Jimi was a Rock Star" was so far out to the left that it falls off the face of the Earth (and we don't miss it). EC has that one fast-forward moment, and BE has none, so BE is better, right?

In thinking about this all I can think is: where in BE is the "Aquarius" (Common spits hard about his craft and definitely non-sullen art); where is the "Electric! Wire! Hustle! Flower!" (Common zaps us with shock therapy using the sharp honesty of his internal paysage moralisé); where is the "New Wave" (Common turns this exploration to the world at large, with the help of spaced out Moog synth and the marvelously affecting crooning by Laetitia Sadier of StereoLab); where is the "I am Music" (Common, still bent on exploration, journeys on all the many axes of 20th century popular music history). There is no one track on BE quite as powerful as these. In achieving greater consistency, Common has also shaved off the peaks a bit. He takes fewer risks, and it shows in the more modest rewards. Continuing with the Roots comparison, even though The Tipping Point is much less experimental than Phrenology, The Roots retain in the former a lot more of the edge that they bled into the latter. See the madhouse genius Sly Stone mash-up "Everybody is a Star" for easy evidence.

In thinking about this all I can think is: where in BE is the "Aquarius" (Common spits hard about his craft and definitely non-sullen art); where is the "Electric! Wire! Hustle! Flower!" (Common zaps us with shock therapy using the sharp honesty of his internal paysage moralisé); where is the "New Wave" (Common turns this exploration to the world at large, with the help of spaced out Moog synth and the marvelously affecting crooning by Laetitia Sadier of StereoLab); where is the "I am Music" (Common, still bent on exploration, journeys on all the many axes of 20th century popular music history). There is no one track on BE quite as powerful as these. In achieving greater consistency, Common has also shaved off the peaks a bit. He takes fewer risks, and it shows in the more modest rewards. Continuing with the Roots comparison, even though The Tipping Point is much less experimental than Phrenology, The Roots retain in the former a lot more of the edge that they bled into the latter. See the madhouse genius Sly Stone mash-up "Everybody is a Star" for easy evidence.

One of the things that fascinates me about EC is that Common drops a lot of easter eggs in the lyrics. The following lines are from "Aquarius".

Playing with yourself, thinking the game is just wealth—

Hot for a minute, watch your name just melt.

Same spot where its joyous is where the pain is felt

As you build and destroy yo remain yourself

They say I'm slept on, now I'm bucking in dreams,

And rhyme with the mind of a hustler's schemes

Listening to that just gives me a frisson. You feel everything Common is saying in the very fabric of the song. Indeed, you feel how Common has just summarized the entire creative impetus behind EC. He wants to build a lasting edifice in art, like Horace, and he doesn't care if the present audience writes him off as a day-dreamer. Common writes into EC a lot of other such apt lines to justify his eclecticism. From "New Wave":

How could a nigga be so scared of change

That's what you hustle for in front of currency exchange

Ya'll rich, we could beef curry in the game

out your mouth: Ain't nobody hurrying my name

[...] Seen hype become fame against the grain become main-

stream. It all seems mundane in the scope of thangs.

I could go on with these examples.

He is a great deal less introspective on BE, and he calls this fact out loudly.

I rap with the passion of Christ, nigga cross me

Took it outer space and niggas thought they'd lost me

I'm back like a chiropract with b-boy survival rap

This ain't '94 Joe we can't go back

The game need a makeover

My man retired, I'm a take over

—from "Chi-City"

He has come out of his dreams in BE, and how he has more material aspirations, as the reference to Jay-Z in the last line hints. And even though I'm rocking out to it f'sure, I just feel that I'm not experiencing the same level of magic as with EC, which certainly "took it outer space" but didn't lose everyone. EC brings me to mind of Gerald Manley Hopkins' poems. What would Hopkins have accomplished if he had the time and encouragement to work on sprung rhythm further? We got some superb poems out of his oeuvre, but nothing that quite matched up to Hopkins' claims for sprung rhythm. You get the sense that he could have built it into a new major branch of metrics in English. I feel that if Common had the time and encouragement to build on EC's approach, we would have not just one superb album, but an entirely new subgenre of hip-hop. Do I exaggerate? The reaction of people whose opinions I respect, to whom I play EC bears me out. I think being a long-time Common fan can give you a touch of tunnel vision when you first listen to it. A fresh ear recognizes the originality and genius.

He has come out of his dreams in BE, and how he has more material aspirations, as the reference to Jay-Z in the last line hints. And even though I'm rocking out to it f'sure, I just feel that I'm not experiencing the same level of magic as with EC, which certainly "took it outer space" but didn't lose everyone. EC brings me to mind of Gerald Manley Hopkins' poems. What would Hopkins have accomplished if he had the time and encouragement to work on sprung rhythm further? We got some superb poems out of his oeuvre, but nothing that quite matched up to Hopkins' claims for sprung rhythm. You get the sense that he could have built it into a new major branch of metrics in English. I feel that if Common had the time and encouragement to build on EC's approach, we would have not just one superb album, but an entirely new subgenre of hip-hop. Do I exaggerate? The reaction of people whose opinions I respect, to whom I play EC bears me out. I think being a long-time Common fan can give you a touch of tunnel vision when you first listen to it. A fresh ear recognizes the originality and genius.

Anyway, LWfC and EC are still my favorite Common albums, with BE close behind, and then SiWaMS followed by Resurrection (although the latter contains one of the all-time Hip-Hop classics in "I Used to Love H.E.R."). Despite Common's disappointing ranking of EC in the interview I mentioned, he also shows that deep down, he knows better.

AllHipHop.com: I know a lot of critics weren't feeling Electric Circus, but I liked the fact that it was very artistic and pushed your creative ability as an MC. Overall though, what has changed between Electric Circus and BE to cause such a distinction between the two albums?

Common: Exactly. I think Electric Circus was just a part of my evolution and my experimentation as an artist and it was kind of like since this was my fifth album I was trying to continue to grow and elevate in what I was doing. To me what changed the most is that I got more in tune with myself and more grounded. Electric Circus was me and I don't apologize for it, it is was it is and it's something I created, so it's a piece of my art. With this album I did something simple and raw because it felt good to me at this time. When I did Electric Circus I wanted to go way out there because I was tired of how Hip-Hop was sounding, that's why I did it like that. But with BE, I actually like some of the Hip-Hop now, but besides that I am more hungry on the creative side.

We were all tired of how Hip-Hop was sounding. We all needed EC. Don't you ever forget that, Common.

AllHipHop.com: How do you think Electric Circus will be treated in time?

Common: It's hard for me to say how it will be looked upon, but I hope that people will look back and say, “Man, this was an innovative album.” I feel that as an artists you should be able to paint a picture, so that even if people aren't feeling it now, they can go back with a different perspective later on and feel what you were saying because they are at a different point in their life. That's my goal when I create music.

Right. Right. And it wouldn't be our beloved Common if he didn't say:

AllHipHop.com: Do sales play into your satisfaction of the albums?

Common: People always looked at me like, “Aw man, you don't care about record sales.” I do want to sell records but I won't give up what I believe in, or take away from the integrity of my music to sell. I'm worth more than that.

But I'm determined to at least close with a bit of appraisal of BE. The master quote above is from "Testify", my favorite track. I cannot listen to this song as background music. I always have to stop and concentrate on listening. I already mentioned the foundational sample, and within that frame lies Common's softly-told story. You're all into the tragedy of this lady's predicament, until the sharply executed twist at the end, when you realize that she's sold her man off to prison. It's brilliantly done. Other favorites for me are "The Corner", "GO!", "Chi-City", "Real People" and "They Say", which I've heard somewhere else before (I can't remember where right now). And oh yeah, Pops is back in "It's your World". I just love Pops. That strong and dignified voice says so much about the nurturing of Common's agile mind. If you're a Hip-Hop fan, or a Soul fan you shouldn't be sleeping on BE, but then again, based on those sales figures, you probably aren't.

But I'm determined to at least close with a bit of appraisal of BE. The master quote above is from "Testify", my favorite track. I cannot listen to this song as background music. I always have to stop and concentrate on listening. I already mentioned the foundational sample, and within that frame lies Common's softly-told story. You're all into the tragedy of this lady's predicament, until the sharply executed twist at the end, when you realize that she's sold her man off to prison. It's brilliantly done. Other favorites for me are "The Corner", "GO!", "Chi-City", "Real People" and "They Say", which I've heard somewhere else before (I can't remember where right now). And oh yeah, Pops is back in "It's your World". I just love Pops. That strong and dignified voice says so much about the nurturing of Common's agile mind. If you're a Hip-Hop fan, or a Soul fan you shouldn't be sleeping on BE, but then again, based on those sales figures, you probably aren't.

[Uche Ogbuji]

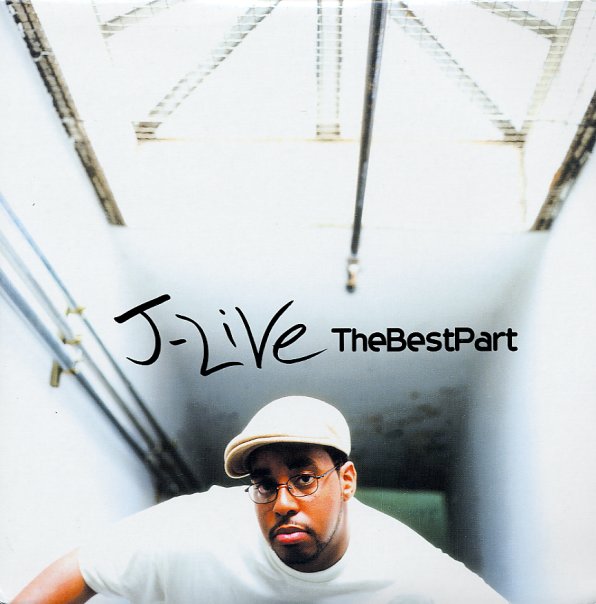

The crowd was a bit slow to get into the mood, which is unusual for Boulder. When J-Live came out to start his set, most folks in the front row had gone off to get drinks, or to hang with the earlier acts, who all got off stage to mingle. It only took the duration of the first song before it became a proper audience for J-Live, though. He did his amazing thing, rocking "MC", "Like this Anna", and "Satisfied?" to the jumping delight of the crowd (and me), there was an impromptu competition in the front row with folks trying to rap along to "One for the Griot". But the highlight of the night was when J-Live did something I've only ever seen him do (I saw him do this trick once before (with Chime and Davina) when he came to CU with Talib Kweli and others for a free

The crowd was a bit slow to get into the mood, which is unusual for Boulder. When J-Live came out to start his set, most folks in the front row had gone off to get drinks, or to hang with the earlier acts, who all got off stage to mingle. It only took the duration of the first song before it became a proper audience for J-Live, though. He did his amazing thing, rocking "MC", "Like this Anna", and "Satisfied?" to the jumping delight of the crowd (and me), there was an impromptu competition in the front row with folks trying to rap along to "One for the Griot". But the highlight of the night was when J-Live did something I've only ever seen him do (I saw him do this trick once before (with Chime and Davina) when he came to CU with Talib Kweli and others for a free  concert). He rapped "Braggin' Writes" while dee-jaying the track at the same time (for the track he used Nas's "Thief's Theme", only the most banging beat of the new millennium), which hardly seems possible. And he didn't just prod occasionally at the wheels of steel: no, he was scratching and cutting almost throughout the song, without missing a beat in his rapping. Amazing!

concert). He rapped "Braggin' Writes" while dee-jaying the track at the same time (for the track he used Nas's "Thief's Theme", only the most banging beat of the new millennium), which hardly seems possible. And he didn't just prod occasionally at the wheels of steel: no, he was scratching and cutting almost throughout the song, without missing a beat in his rapping. Amazing! One more quote to leave off with. This one Vast Aire's from an

One more quote to leave off with. This one Vast Aire's from an  Common is one of my favorite musicians, and so I'm really pleased to see his new baby,

Common is one of my favorite musicians, and so I'm really pleased to see his new baby,  In thinking about this all I can think is: where in BE is the "Aquarius" (Common spits hard about his craft and definitely non-sullen art); where is the "Electric! Wire! Hustle! Flower!" (Common zaps us with shock therapy using the sharp honesty of his internal paysage moralisé); where is the "New Wave" (Common turns this exploration to the world at large, with the help of spaced out Moog synth and the marvelously affecting crooning by Laetitia Sadier of StereoLab); where is the "I am Music" (Common, still bent on exploration, journeys on all the many axes of 20th century popular music history). There is no one track on BE quite as powerful as these. In achieving greater consistency, Common has also shaved off the peaks a bit. He takes fewer risks, and it shows in the more modest rewards. Continuing with the Roots comparison, even though The Tipping Point is much less experimental than Phrenology, The Roots retain in the former a lot more of the edge that they bled into the latter. See the madhouse genius Sly Stone mash-up "Everybody is a Star" for easy evidence.

In thinking about this all I can think is: where in BE is the "Aquarius" (Common spits hard about his craft and definitely non-sullen art); where is the "Electric! Wire! Hustle! Flower!" (Common zaps us with shock therapy using the sharp honesty of his internal paysage moralisé); where is the "New Wave" (Common turns this exploration to the world at large, with the help of spaced out Moog synth and the marvelously affecting crooning by Laetitia Sadier of StereoLab); where is the "I am Music" (Common, still bent on exploration, journeys on all the many axes of 20th century popular music history). There is no one track on BE quite as powerful as these. In achieving greater consistency, Common has also shaved off the peaks a bit. He takes fewer risks, and it shows in the more modest rewards. Continuing with the Roots comparison, even though The Tipping Point is much less experimental than Phrenology, The Roots retain in the former a lot more of the edge that they bled into the latter. See the madhouse genius Sly Stone mash-up "Everybody is a Star" for easy evidence. He has come out of his dreams in BE, and how he has more material aspirations, as the reference to Jay-Z in the last line hints. And even though I'm rocking out to it f'sure, I just feel that I'm not experiencing the same level of magic as with EC, which certainly "took it outer space" but didn't lose everyone. EC brings me to mind of Gerald Manley Hopkins' poems. What would Hopkins have accomplished if he had the time and encouragement to work on sprung rhythm further? We got some superb poems out of his oeuvre, but nothing that quite matched up to Hopkins' claims for sprung rhythm. You get the sense that he could have built it into a new major branch of metrics in English. I feel that if Common had the time and encouragement to build on EC's approach, we would have not just one superb album, but an entirely new subgenre of hip-hop. Do I exaggerate? The reaction of people whose opinions I respect, to whom I play EC bears me out. I think being a long-time Common fan can give you a touch of tunnel vision when you first listen to it. A fresh ear recognizes the originality and genius.

He has come out of his dreams in BE, and how he has more material aspirations, as the reference to Jay-Z in the last line hints. And even though I'm rocking out to it f'sure, I just feel that I'm not experiencing the same level of magic as with EC, which certainly "took it outer space" but didn't lose everyone. EC brings me to mind of Gerald Manley Hopkins' poems. What would Hopkins have accomplished if he had the time and encouragement to work on sprung rhythm further? We got some superb poems out of his oeuvre, but nothing that quite matched up to Hopkins' claims for sprung rhythm. You get the sense that he could have built it into a new major branch of metrics in English. I feel that if Common had the time and encouragement to build on EC's approach, we would have not just one superb album, but an entirely new subgenre of hip-hop. Do I exaggerate? The reaction of people whose opinions I respect, to whom I play EC bears me out. I think being a long-time Common fan can give you a touch of tunnel vision when you first listen to it. A fresh ear recognizes the originality and genius. But I'm determined to at least close with a bit of appraisal of BE. The master quote above is from "Testify", my favorite track. I cannot listen to this song as background music. I always have to stop and concentrate on listening. I already mentioned the foundational sample, and within that frame lies Common's softly-told story. You're all into the tragedy of this lady's predicament, until the sharply executed twist at the end, when you realize that she's sold her man off to prison. It's brilliantly done. Other favorites for me are "The Corner", "GO!", "Chi-City", "Real People" and "They Say", which I've heard somewhere else before (I can't remember where right now). And oh yeah, Pops is back in "It's your World". I just love Pops. That strong and dignified voice says so much about the nurturing of Common's agile mind. If you're a Hip-Hop fan, or a Soul fan you shouldn't be sleeping on BE, but then again, based on those sales figures, you probably aren't.

But I'm determined to at least close with a bit of appraisal of BE. The master quote above is from "Testify", my favorite track. I cannot listen to this song as background music. I always have to stop and concentrate on listening. I already mentioned the foundational sample, and within that frame lies Common's softly-told story. You're all into the tragedy of this lady's predicament, until the sharply executed twist at the end, when you realize that she's sold her man off to prison. It's brilliantly done. Other favorites for me are "The Corner", "GO!", "Chi-City", "Real People" and "They Say", which I've heard somewhere else before (I can't remember where right now). And oh yeah, Pops is back in "It's your World". I just love Pops. That strong and dignified voice says so much about the nurturing of Common's agile mind. If you're a Hip-Hop fan, or a Soul fan you shouldn't be sleeping on BE, but then again, based on those sales figures, you probably aren't.