He scarce had ceas't when the superior Fiend

Was moving toward the shoar; his ponderous shield

Ethereal temper, massy, large, and round

Behind him cast; the broad circumferance

Hung on his shoulders like the Moon, whose Orb

Through Optic Glass the Tuscan Artist views

At Ev'ning from the top of Fesole,

Or in Valdarno, to descry new Lands,

Rivers or Mountains in her spotty Globe.

His Spear, to equal which the tallest Pine

Hewn on Norwegian hills, to be the

Mast Of some great Ammiral, were but a wand,

He walkd with to support uneasie steps,

Over the burning Marle, not like those steps

On Heavns Azure, and the torrid Clime

Smote on him sore besides, vaulted with Fire;

Nathless he so endur'd, till on the Beach

Of that inflamed Sea, he stood and call'd

His Legions, angel Forms, who lay intrans't

Thick as Autumnal Leaves that strow the Brooks

In Vallombrosa, where th'Etrurian shades

High overarcht imbowr;…

—John Milton—from Book 1, Paradise Lost, quoted in "Eliot & Milton Studies", Sherry, Beverley, Versification 5 (2010)

I finally caught up with the new edition of Versification, (presently the front page of the site) a bit of Sunday morning therapy through prosody. The first article, on the possibly exaggerated modernist credentials of Emily Dickinson, is a bizarre thing that seems to want to be edgy and cool, spending time comparing Dickinson to a visual poet who played at Möbius strip-mining with Eikon Basilike (a bit of a look-forward to the later Milton piece), and with whom there is no conceivable connection. It also does go on about an apparent saw that you can sing all Dickinson's poems to the theme of Gilligan's Island, an rather sophomoric bit of pablum. The second article is a punctilious, frequently baffling, over-argued, and generally dreary exposition of pervasive syllabic verse in W.H. Auden.

Luckily I persevered because the last two pieces were true delights. The last article is a review of

Latin Word Order: Structured Meaning and Information, by Devine and Stephens (Oxford University Press, 2006). It sounds like a wonderful volume, and I've added it to my Amazon wish list for whenever I can afford the $85. Any book that dwells with insight over the contrasting word order of

socerum tuae filiae versus

filiae tuae socerum is irresistible to a language geek.

The third article,

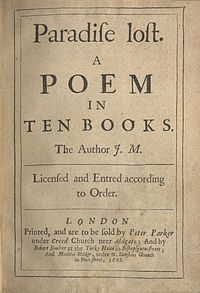

"The Legacy of T.S. Eliot to Milton Studies" discusses "the Milton controversy" of the twentieth century, triggered by Eliot's early attacks on Milton. I've never seen the controversy as a big deal. In my own taste I go from enjoying Milton's earlier "L'Allegro" and "Il Penseroso" to admiring but not at all enjoying his

magnum opus "Paradise Lost." I certainly understand the urge by Eliot and cohort to elevate Donne and the Metaphysics, cavalier spirits of rotund urbanity, compared to the dour asceticism of old Roundhead Milton (and yes, I know The New Critics would have shied away from such biographical tinting, but I'm not really one of them), but many of their specific criticisms have never really been credible, and this article presents a useful survey of the vigorous response to the anti-Milton camp.

One flaw I found is in Sherry's lumping in with the New Critics Robert Graves's own anti-Miltonism, best known from his novel

Wife to Mr Milton. It's important to separate Grave's objections, which were more on moral grounds tha

n on prosodic, from Eliot, whose objections focused on his poetics. The Graves who wrote the "These be thy Gods, O Israel!" lecture would be furious to find himself lumped in with the agenda of "the 'most 'significant' modern writers." Mr. Triple Goddess Graves could never tolerate any betrayal of the women in a poet's life, despite the fact that his own relationship with Laura Riding included every usual human frailty. As far as he was concerned, Eliot's sins were even more foetid than Milton's.

Graves's own words, in "The Ghost of Milton," which he wrote in response to criticism of his treatment of Milton in

Wife to Mr Milton:

My attitude to Milton must not be misunderstood. A man may rebel against the current morality of his age and still be a true poet, because a higher morality than the current is entailed upon all poets whenever and wherever they live: the morality of love. Though the quality of love in a painter's work, o a musician's, will endear him to his public, he can be a true painter or musician even if his incapacity for love has turned him into a devil. But without love he cannot be a poet in the final sense. Shakespeare sinned greatly against current morality, but he loved greatly. Milton's sins were petty by comparison, but his lack of love, for all his rhetorical championship of love against lust, makes him detestable.

With all possible deference to his admirers, Milton was not a great poet, in the sense in which Shakespeare was great. He was a minor poet with a remarkable ear for music, before diabolic ambition impelled him to renounce the true Muse and bloat himself up, like Virgil (another minor poet with the same musical gift) into a towering, rugged major poet. There is strong evidence that he consciously composed only a part of Paradise Lost; the rest was communicated to him by what he regarded a supernatural agency.

The effect of Paradise Lost on sensitive readers is, of course, overpowering. But is the function of poetry to overpower? To be overpowered is to accept spiritual defeat. Shakespeare never overpowers: he raises up. To put the matter in simple terms, so as not to get involved in the language of the morbid psychologist: it was not the Holy Ghost that dictated Paradise Lost—the poem which has caused more unhappiness, to the young especially, than any other in the language—but Satan the protagonist, demon of pride. The majesty of certain passages is superhuman, but their effect is finally depressing and therefore evil Parts of the poem, as for example his accounts of the rebel angels' military tactics with concealed artillery, and of the architecture of Hell, are downright vulgar: vulgarity and classical vapidity are characteristic of the passages which intervene between the high flights, the communicated diabolisms.

This underscores the moral nature of Grave's objections. Graves admits Milton's "remarkabl e ear for music," which Eliot accepted only much later, when he famously took back much of his anti-Miltonism. They may both have scorned Milton, but their motivations and arguments were entirely different.

In fairness I should point out that later in the above Essay Graves says, with regard to

Lycidas:

the sound of the poem is magnificent; only the sense is deficient.

Which seems to echo Eliot's objections, but Graves goes on to clarify his quarrel with the sense, and it turns out to be a Pagan Celtic sanctimony every bit as fulsome as the Christian sanctimony of his quarrel with Paradise Lost. Again nothing to corroborate Eliot's points in substance.

Eliot's points always carried on far too much of Pope's nonsense in "An Essay on Criticism," a reasonably enjoyable poem as long as you never make the mistake of thinking it has any instructive value for actual criticism (another area in which I depart from Graves, who insists that a poem must be true and apt in order to be enjoyable). Eliot seems to have slavishly applied Pope's petty standards for marking sound against sense, and became thoroughly misled. Sherry uses the main quote of this post to debunk Eliot's claim, and I think she makes a decisive point, except that even she cannot excuse the sheer drudgery of

Paradise Lost in the large, which, if you ignore the moral overtones, I think Graves covers in his charge that it is "the poem which has caused more unhappiness, to the young especially, than any other in the language."

It's also worth pointing out the undue attention Sherry as well as Eliot and other critics before her, pay to the influence of Milton's blindness on his poetic faculties, which is more of that infuriating 20th century habit of conflating the nature of language, the senses and experience in ridiculously simplistic ways. Graves is far more sensible on the matter, accusing Milton himself, if anything, of making too vulgar a use of his blindness as a device to encourage approbation. You would expect a tidy New Critic such as Eliot to know better than to hypothesize extravagantly about that anatomical detail.

I suppose the upshot of today's reading is that I'll be spending a bit more time revisiting Milton's actual text, but unless I suddenly find him much less soporific than I did when I made a serious attempt to appreciate him in the past, I'm not going to pretend I have the stamina for much of his work. The point of escaping into poetry is to enjoy the amenities of the alcove, a notion I would have thought was obvious, but which I've had to suggest to others several times, recently.

Thanks very much to those responsible for Versification for having giving me these hours of enjoyment and reflection. It must be a truly thankless task to produce a journal on Prosody these days.

✄ ✄ ✄

Editorial note: You might have noticed I expanded the title of this post beyond the customary "Quotīdiē." I plan to continue doing so.