My escape

Had become such a hunted thing

Sleepless, hopeless, all its dreams exhausted,

Only wanting to be recaptured, only

Wanting to drop, out of its vacuum.

Two days of dangling nothing. Two days gratis.

Two days in no calendar, but stolen

From no world,

Beyond actuality, feeling, or name.

—from "Last Letter" by Ted Hughes

When I consider Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath I am not interested in drama, nor in the US versus the UK in arts, nor in feminism. I am interested in poetry. I said as much

a couple of weeks ago when I discussed hearing about the newly discovered Hughes poem "Last Letter." I have always been infuriated at how feminism and silly cultural rivalries have overshadowed the work of two great poets who happened to share a sort of archetypal tragedy. As I said in

"Slender Mitochondrial Strand" I am not connected to the Hughes or Plath families, and it seems only proper to leave their private lives alone. That said, it has always seemed to me that the conjunction of those two poets enhanced both their work. Plath's best work by far came after her marriage, and much of my favorite work from Hughes is in

Wodwo and

Lupercal, and as I gather dating from around the years of their tumultuous romance. I don't know when Hughes picked up a tendency towards slack passages, but he certainly did at some point, and it has for me definitely affected much of his later work. "Last Letter" is no exception.

According to my intention stated in the previous piece, I headed to the CU Boulder Library which according to WorldCat carries a subscription to the

New Statesman magazine, the exclusive publisher of "Last Letter." I'd hoped to own the issue, so prior to my trip to the library I checked several newsstands, including the one at Barnes and Nobles, and the famous Eads of Boulder, but no one seemed to carry the British journal. I was quite excited to find the issue in the CU shelves, and sat down to read it.

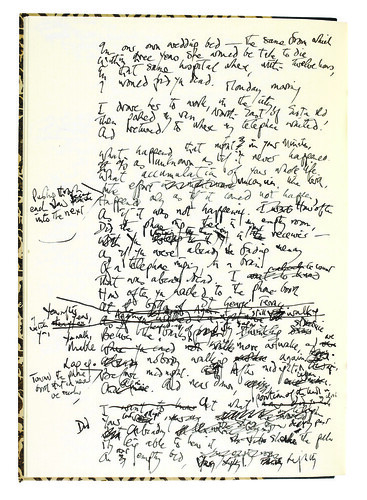

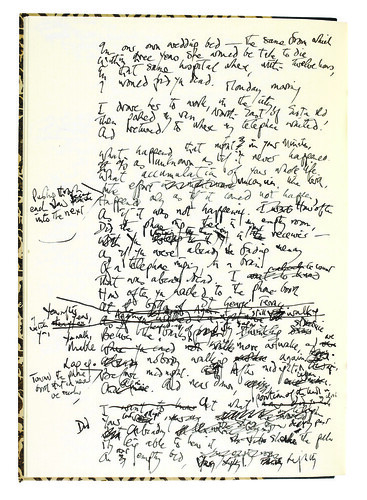

"Last Letter" is a decent poem, or if I am to be frank in characterizing it, a brilliant poem cut into bits which are sprinkled among passages of prosaic exposition. You very quickly see in the poem what is carved in marble and what is knuckled into butter. The head quote, above, is one of the larger bits of sculptured marble, and the thirteen lines that follow it. So is the part that was quoted in one of the teasers for the new poem, and which I quoted in the last piece.

What happened that night, inside your hours

Is as unknown as if it never happened.

What accumulation of your whole life,

Like effort unconscious, like birth

Pushing through the membrane of each slow second

Into the next, happened

Only as if it could not happen

As if it was not happening.

It was a canny edit, that, in the middle of a line, as I found reading the whole poem, with the end of that same line losing the energy of what preceded it, continuing into a sighting of Plath's ghost, which slips between marble and butter, but ends solidly enough, concluding with the two lines:

Before midnight. After midnight. Again.

Again. Again. And, near dawn, again.

The stretch after that is the final bit of the poem, and is again a marble/butter hybrid. Going back to the beginning of the poem (I count 154 lines in all), the first 40 lines are uneven, and then it explodes into the head quote, which begins at line 41. That strong passage continues to line 62, but I only quoted a part of it out of respect for the publisher. Lines 61 and 62 are:

Their obsessed in and out. Two women

Each with her needle.

This immediately brought me to mind the "Prufrock" refrain:

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

I already mentioned how the passage starting with line 112 ("What happened that night, inside your hours,") reminded me of The Four Quartets, and this is striking because most of my favorite Hughes is nothing like Eliot. Am I dipping into the soap opera nonsense when I ponder that Hughes might be mouthing echoes from Eliot's tortured relationship with Vivienne?

Line 63 begins the longest slack passage, which lasts until the hard shore of line 112.

I'm very glad I sought out the poem. Even the prosaic parts are written by a master writer, and I can appreciate them for the connective exposition they are. I don't know that the soap opera fans will find a lot of new dramatic ground here that was not covered in

Birthday Letters, though I don't doubt that they'll pick out some juicy nuggets of gossip. From a poetical perspective, "Last Letter" is a narrative that picks its moment to seize upon finely crafted poetry to share a keen sense of how time seems a wretched tapestry when considered around a moment of accident and loss. The discovery is not just more hype in the Hughes/Plath line, but a genuine gain for poetry.